Glæd Geol!

WHAT IS YULE?

Yule was a celebration of Germanic origin, celebrated by both the Norse and the Anglo-Saxons. Yule marked the time of year when the days began to lengthen again after the winter solstice, symbolizing the rebirth of the sun, a moment particularly felt by those northern European populations who suffered most from the long dark days of winter.

Winter was a particularly difficult time where people most often depended on the supplies made during the other seasons and the support of the community could be essential for survival.

The origin of the word Yule comes from the Germanic *jehwlan > jól (Norse)> jul (Danish and Swedish)> jul or jol (Norwegian) in Anglo-Saxon géol or géohol and géola or géoli.

We are not, unfortunately, certain about the origins of the name, for many scholars (including Grimm) it may derive from the Norse hjól meaning ‘wheel’, for others it may mean ‘time of revelry’ from the Anglo-Saxon gylian or giellan meaning shouting or from gýlan meaning ‘to party’.

In the archaic and poetic language of modern English, words such as yule-tide or géol / géohol and yule-log or géolstocc are still used, the former meaning the Yule festive period and géola or géoli the Yule month, the latter meaning a special tree trunk that was selected to be burnt during the Yule festivity.

Yule was the festival marking mid-winter, an event to be spent in the company of friends and relatives where people celebrated together.

YULE IN TOLKIEN’S LEGENDARIUM

Tolkien was well aware of this feast, not only as a philologist, glottologist and linguist, but also as a passionate and avid researcher of folk tales and legends.

Like many other historical and legendary elements, Yule also becomes part of the Tolkenian legendarium where various references to this feast can be found in literary works.

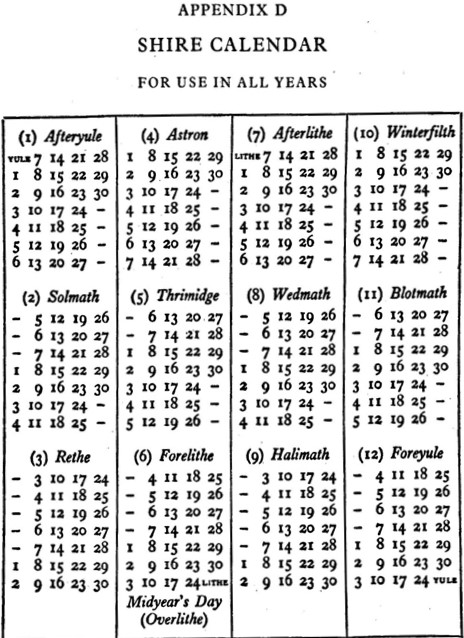

In “Appendix D” to The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien, expressly mentions Yule or Midwinter (midwinter feast) when we are presented with the Hobbit calendar.

“Each year began with the first day of the week, Saturday, and ended with the last day of the week, Friday. The Midsummer Day (also called Midsummer Day), and, in leap years, the Superlithe, was a separate part, and was not named after any of the days of the week. The Lithe preceding the Midsummer Day was called the First Lithe, the one following the Midsummer Day was called the Second Lithe. The day with which the year ended was called First New Year (Midwinter); the day with which it began, Second New Year (Midwinter). The Superlithe was an important feast day, but it never fell in the years relevant to the history of the Ring. Instead, it fell in 1420, the year of the famous harvest and enchanting summer, and it appears that the festivities of that year, unprecedented in Hobbit memory, exceeded all terms of comparison.“

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Appendix D, “The Calendars”

It immediately emerges that for the Hobbits “Lithe and New Year (Midwinter) were the main holidays”, and as is easy to guess from the use of the plural these holidays lasted several days, in particular, “the New Year (Midwinter) period lasted six days in all, including the last three and the first three of each year.”

Today, we would say it was a melting pot of different cultures that the Hobbits come into contact with, but unlike the Eldar and Numenoreans peoples with whom they are in closer contact since settling in the Shire, this was divided into 30-day months, to which were added these days of holidays that were independent of the month’s day count.

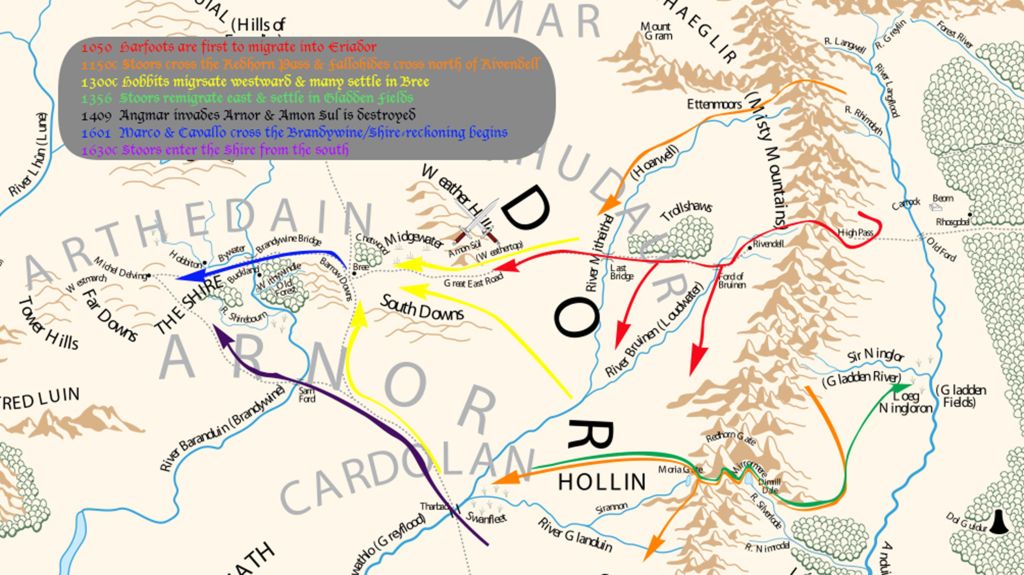

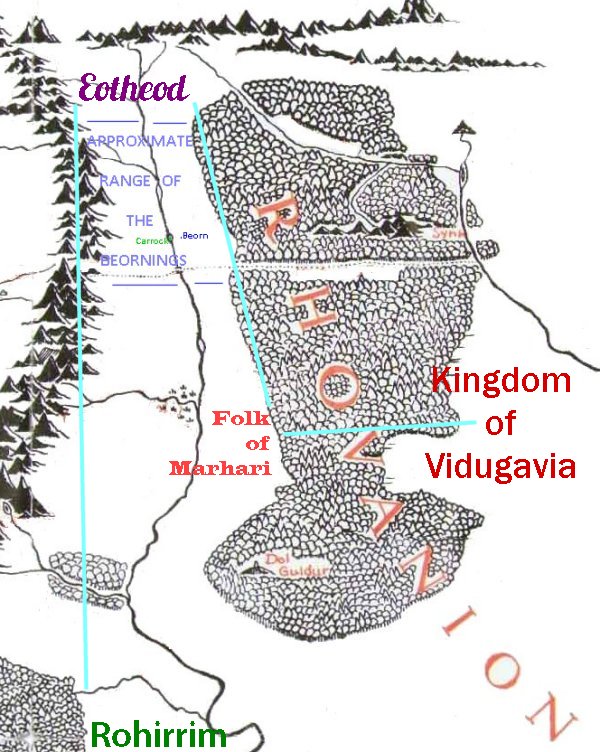

In delving into the names of the months, another interesting passage for our research stands out, Tolkien tells us that the nomenclature of these months: “did not follow the customs of the Westron and instead remained faithful to ancient local names, which they had apparently learnt in ancient times from the Men of the valleys of the Anduin; in any case, very similar names could be found in the Valley and in Rohan.”

Among the 12 months of the Hobbit calendar the month before and after the feast was named after the same feast for the Lithe we see in fact:

– Forelithe (in Anglo-Saxon Æ’rra Líþa) before Lithe,

– Afterlithe (in Anglo-Saxon Æftera Líþa), after Lithe

While for New Year (Midwinter) we find

– Afteryule (in Anglo-Saxon Æftera Géola), before Yule,

– Foreyule (in Anglo-Saxon Æ’rra Géola), after Yule.

According to the Hobbit calendar, the two Yule days always occupied the same day of the week, namely Highday and Sterday (Friday and Saturday).

A further reference to this feast is found in the “Guide to the Names in the Lord of the Rings”, the author is keen to emphasize two things, firstly this feast is not an Elvish custom and secondly it is not a word of the Common tongue (Ovestron).

This celebration originates from the Northmen of Rhovanion, people with a strong Germanic inspiration in the Tolkien imagery, and although he does not describe in detail applicable customs and traditions, we can deduce with good approximation that they must always be inspired by the Germanic world.

As those who follow us well know, the Rohirrim in Tolkien embody the Old English spirit of the early Middle Ages the founder of the kingdom of Rohan, was Eorl the Younger who led the Éothéod, a lineage of Northmen, there into Calenardhon, bringing with him not only his people but also the traditions and culture of Northmen.

The connection between Yule, the Germanic world and Rohan is not only recalled by the author himself but also intrinsic in the ethnogenesis of this population.

The Yule Party for the Germans

Hwaet!

Bede the Venerable, in his work De ratione temporum (725) in describing the most important calendars of his time, also analyses the Anglo-Saxon one. He argues that the Anglo-Saxons called the months of December and January by the same name, namely Giuli (“…December Giuli, eodem Januarius nomine, vocatur”, Bede), and that they celebrated the beginning of the New Year on 25 December, the same day as the birth of Jesus, but they used to call this night Modranecht or “the night of the mother”, a night when they probably (“… ut suspicamur’, Bede) used to celebrate these ‘mothers’, although we do not have many sources on this and it is all still under discussion, as the medievalist Dunn argues.

But how was this feast celebrated by the Anglo-Saxons?

On this point, unfortunately, we have no certainties but a few testimonies.

Perhaps the clearest representation of what the Yule might have been in the Anglo-Saxon/Norse pagan world is given to us by a Christian, Bede, who in his Ecclesiastical History, Book II, Chapter XIII, gives us a passage where he describes the court of a pagan King Edwin:

“O king, the present life of men on earth seems to me, in comparison with the time that is unknown to us, as if you were sitting down to dinner with your men and councillors in winter, with a good fire burning on the hearth in the middle of the hall and everyone inside well warmed, while outside raging storms of winter rain and snow are raging. A sparrow comes flying swiftly across the hall; it enters through one door and soon leaves through the other. During the time he is inside, the winter storms cannot touch him; but after the briefest moment of clear weather, he vanishes from your sight, quickly returning from winter to winter. In the same way, this life of men appears for a brief moment; what came before, or what will come after, we do not know at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine offers something more certain, it seems worthy of being followed.”

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, Book II, Chapter XII)

At this point, we begin to analyze some typical elements of Yule celebration: first, it was a social moment to be spent as a community in the common room in front of the fire. The worst imaginable fate that the Anglo-Saxon mind can conceive would be facing winter without the comfort of the mead-hall, we can find this, albeit through different circumstances, in The Wanderer and in The Beowulf.

The ‘mead-hall’ (in Anglo-Saxon Meduseld, beorsele, etc.) the place where people celebrated and stayed together during the long, cold winters was the mead hall, like the Meduseld of Edoras.

The tradition of the Yule log (yule-log) – a special long-aged log specially preserved to be burnt slowly in mid-winter – may have started in Anglo-Saxon times. In some versions of this tradition, the log was kept burning continuously until the twelfth night.

The time of drinking and toasting must have been an essential part of the festivities invoked with the greeting ‘wes hál / wes thu hál’, which we find again in Rohan for example, when Éomer says to Théoden: “Westu Théoden hal! ‘ in The Lord of the Rings, he echoes Beowulf’s appeal to Hrothgar in the Old English poem Beowulf: ‘Wæs þu, Hroðgar, hal’ (Beowulf, l. 407), ‘May you be in health, Hrothgar’.

Later folk traditions, including processions/field blessings, door-to-door greetings and Christmas carols, known collectively as ‘wassailing’ are first highlighted in the early medieval period and may have begun, in some form, as part of the Anglo-Saxon pagan yule.

Another tradition is that of decorating the mead-hall during winter periods, with specific plants such as holly, ivy, mistletoe and perhaps yew. These plants would have served both to embellish the banquet hall of the feast giving a bit of happiness and cheerfulness, counteracting the cold and dark days, and to cure illness typical of the season (even if only through the act of breathing in their aromas), and as a connection with sacredness, as reported in Anglo-Saxon herbals such as the Lacnunga (in which we even have a reference to Woden).

Winter and cold, especially in the higher latitudes, seem to be synonymous with anguish and despair (Wanderer), sadness as reported earlier. Further north in Gylfanning (The Deception of Gylfi), it is said that the great winter Fimbulvetr will come, then three winters will anticipate the coming of Ragnarǫk, (‘the doom of the gods’, i.e. the end of the world and its rebirth, according to Norse mythology) and then three more increasingly cold winters.

Also in the Norse sagas, as in the Anglo-Saxon poems, winter is very much present and fortunately, in some of these sagas reference is made to the feast of Jól. Numerous stories of ghosts, ogres, satyrs and ‘goblins’ (Jóla-sveinar) were also linked to this feast; the colder and darker it got, the more power these monstrous figures gained in the stories told around the hearth. In the saga of Grettir Ásmundarson, for instance, a shepherd begins a mutually fatal battle on the eve of Yule with an ‘evil creature’ that besieges his farm. In reality this creature is none other than the son of the old owner who comes back to life from the dead as a draugr, to damage property and terrorise the population at night.

Another saga to be mentioned in connection with Yule is the Saga of the Eyri people (Eyrbyggja saga), which tells how a family is attacked just before Yule by a supernatural seal coming out of the chimney. Every attempt to batter the seal only makes it rise even higher, until a boy hits it with a club and the seal falls ‘as if it were hammering a nail’.

Small but interesting Norse curiosities:

The day after Yule was called atfanga-dagr Jóla, on this day provisions were made and fresh beer was brewed: Jóla-öl.

As for Yule games, we can find them in the Norse and Danish words Jule-buk, Jola-geit = Yule goat, Danish Jule-leg = Yule game (see Ivar Aasen’s dictionary).

Bibliography and website:

- Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

- Guide to the Names in the Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

- Beowulf a cura di Ludovica Koch, Einaudi ed.

- Edda di Snorri Sturluson, a cura di Giorgio Dolfini, Adelphi ed.

- The Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons, Marylinn Dunn

- Pollington, Stephen. “The Mead-Hall: Fighting and Feasting in Anglo-Saxon Society.” Medieval Warfare, vol. 2, no. 5, 2012, pp. 47–52. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48578043. Accessed 20 Dec. 2023.

- Saga di Grettir Ásmundarson

- Saga del popolo di Eyri

- https://www.jrrtolkien.it/2015/12/24/yule-la-festivita-invernale-degli-hobbit/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Draugr

- https://bifrost.it/

- https://cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/jol

- https://www.thegns.org/blog/yule?fbclid=IwAR2_HKNmnalU8XCt98bGRtccLd0ZK-PK4eUx_UkbFFzu8wSZ5skGa-lQH6k

- http://thethegns.blogspot.com/2012/12/yule_25.html

- https://www.abdn.ac.uk/news/10265/

- https://cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/jol

Lascia un commento